Citizen Participation Project – Tracking Flower and Leaf Emergence in the Riparian Trees of Arizona

Frank Reichenbacher • frankr1@arizona.edu • 1 November 2022

Introduction

This How To provides a list of procedures and all the information needed for a citizen scientists to participate in a one-year study of the pattern and timing of flower and leaf emergence in nine broadleaf deciduous riparian trees in Arizona. Your observations will be used to answer the question: Do the trees flower before they leaf, or leaf before they flower? During the data gathering process and after we have obtained and analyzed our data, we will explore reasons for the patterns we find and attempt to answer a follow-up question: Why would trees flower before they leaf or leaf before they flower?

The Trees

We are interested in nine species of broadleaf deciduous riparian trees.

- BROADLEAF – As opposed to needles (pines and spruces) or scales (junipers and tamarisk).

- DECIDUOUS – All leaves are dropped in the autumn and all new leaves are produced in spring.

- RIPARIAN – Grow along streams and rivers.

- TREE – At least 4-5 meters tall at maturity and with a single trunk or only a few stems.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Tree Description | SEINet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fremont Cottonwood | Populus fremontii | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Narrowleaf Cottonwood | Populus angustifolia | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Goodding Willow | Salix gooddingii | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Bonpland Willow | Salix bonplandiana | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Arizona Sycamore | Platanus wrightii | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Velvet Ash | Fraxinus velutina | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Arizona Black Walnut | Juglans major | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Arizona Alder | Alnus oblongifolia | View tree description | View on SEINet |

| Box Elder | Acer negundo | View tree description | View on SEINet |

This is less than one-quarter of a percent of the nearly 4,000 species of plants that comprise the flora of Arizona. But for many reasons these nine are among the most important and valuable.

The photographs in the tree descriptions were taken from the online botanical database, SEINet (Southwestern Environmental Information Network, https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet). We will review a few of the many useful features of SEINet later, but first note that I do not have images of the same features (tree, male/female flowers/fruits, stems, leaves) for every species. This is not for a want of looking. Hopefully, one result of this project will be to fill in these gaps at SEINet with some of your images.

SEINet

The Southwestern Environmental Information Network, SEINet for short, is an online resource of immeasurable value to the botanists and interested non-scientists of the Southwest. It delivers occurrence data from hundreds of thousands of specimens and observations housed at or reported to dozens of institutions from across North America.

To search the collections, go here: https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet/collections/index.php

And click on the “Search” button. You can input a scientific name, genus and species, or just the genus name or a family name. Inputting “Populus fremontii” serves up 2,889 records. About 5-15% of SEINet dried plant specimen records have been scanned by their respective institutions and may be viewed. You can also view the records in a Google Maps interface. Most species come with links to images and descriptions as well.

Before you head out into the field, in fact, long before you head out, I would suggest searching SEINet for the riparian trees in the place you want to go. For example, a SEINet record of a specimen collected by Meg Quinn on April 9, 2003, from along the Verde River in Tuzigoot National Monument includes the scanned specimen which clearly shows new female flowers. You should be able, therefore, to count on finding cottonwood trees in flower in early April yourself at that location, but keep in mind that flowering times vary quite considerably with elevation even in the same species.

Where To Find Them

You will find the best developed riparian vegetation along the larger perennial streams. The big rivers – Colorado, Gila, and Salt – have lost their riparian vegetation and most of their waters, but even there, one can find the occasional cottonwood or willow tree.

You may already know where there are good stands of riparian vegetation in your area – Sabino Creek, Seven Springs, Sycamore Canyon, Cave Creek, Madera Canyon, Burro Creek, the Little Colorado. If, however, you want to explore someplace new, you may want to check out an up-to-date and very accurate map of the perennial waters of Arizona (https://azconservation.org/science/?gis) made available by the Arizona Nature Conservancy.

Go here:

https://tnc.maps.arcgis.com/apps/mapviewer/index.html?webmap=2785577a173e424582f39f338b980b1c

What To Record

Most cameras sold today in smartphone and tablets are GPS enabled which means that longitude and latitude coordinates as well as elevation are baked into the image file. Send me the original image files. If you edit, or otherwise alter the file, GPS data may not be included. Attach the image files to an email, or copy them to a USB stick or send them to a DropBox folder, and send them to me. I can create a DropBox folder specifically for you in my account and set it so only you can upload files to it. The date the image was created is also embedded so I should be able to match images with data. If there are too many images or if you need help, let me know and we can work out something.

The Minimum Data

I will need to know the best way to contact you if I have questions about your submittal. Email is preferred.

The minimum requirement for a single complete observation is this:

- Observer’s name(s)

- Date

- Location (see above for GPS in image files)

- Species (must be one of our nine riparian trees)

- Photograph showing leaves and flowers to illustrate the condition in item 6, below.

- Condition:

- Leaves: none (N), just emerging (E), fully developed (D)

- Flowers:

- Male: none (N), just emerging (E), fully developed (D)

- Female: none (N), just emerging (E), fully developed (D)

- Fruits: none (N), just emerging (E), fully developed (D)

Bring binoculars. It may be difficult to find a tree with flowering branches low enough for you to get a good look at emerging flowers and leaves.

Write it down on a napkin, or in a gold-embossed Hallmark Journal, or looseleaf paper, or on a pillowcase, Styrofoam cup, or, in short, just about anything, and send it to me somehow. As above, I need photos. If you know your camera device is not GPS-enabled send me digital image files by whatever means convenient. Negative observations are useful, so if you go to a tree and it is completely leafless or fully leafed out and with no evident sign of flowers or fruits, that is a legitimate data point. You can send me one observation of one tree at one place and no more and I will be grateful. But the more the better. Walk along the stream recording observations as you go.

The Next Level

Find three mature trees of one of the nine riparian tree species, give them ID numbers (eg. AA1 for Arizona Alder 1) and visit them as often as possible during the reproductive season. (Keep in mind that “spring” in the mountains is “early summer” in the deserts.) Follow these three trees, noting their condition and recording the minimum data listed above at each visit plus a photograph of the whole tree and a close-up of emerging leaves and flowers to illustrate the condition noted in item 6, above.

The trees cannot be close together. Trees of the same species close together are very likely closely related, perhaps parent/offspring or siblings. The trees should be at least 50 m apart in order to obtain a representative sample of heritable variation in the population.

You will also need to try to find your three trees and mark them and then begin taking observations before they have begun to leaf and flower. This is when accessing records on SEINet becomes important. Use it to plan your contribution to the project.

Why three? We just need some level of redundancy. Observations of just one individual might produce atypical results, but two more individuals likely not closely related should be reliable.

All In

This is an expanded version of the Next Level. Datasheets are similar but we ask for a judgement of the percentage of the tree in leaf, bloom, and fruit at each visit. (Definitely bring binoculars.) It is a judgement you will likely have to revise as you go during the course of your observation program and may require revising some of your earlier observations. The reason is that you might not be able to tell what 50% in leaf, or 75% in flower means until after the tree has reached and passed 100% leaf and flower. A plant is hardly ever fully in bloom, some parts will support more than others, but you won’t know that until after it is all done.

The recommended schedule of visits will be the same. An important added task is to add your contribution to SEINet. You will establish a SEINet account, input your data, and upload your best images for the one visit that best represents the height of flower emergence for each of the trees you follow.

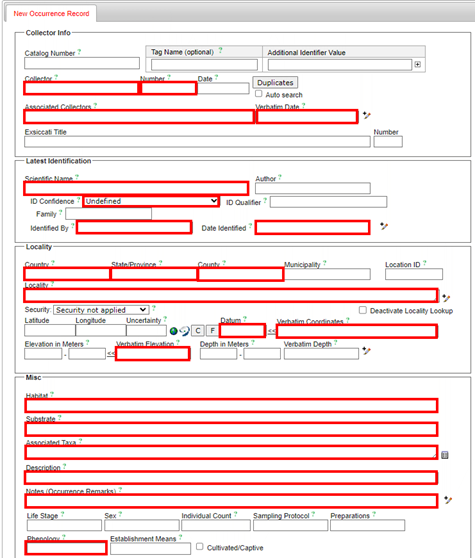

How to Fill In the SEINet Occurrence Form

Much of the power incorporated into SEINet comes from its wide use as a database repository for the many dried pressed plant specimens housed at research institutions across the continent. In addition to the database of curated specimens SEINet also acts as a repository for observations. Go online set up your account and please enter your observations. Having said that, the online occurrence entry form is not really set up for multiple observations of a single plant over time. I suggest, therefore, that you enter one observation for each tree you observe recording the date of peak flowering. That means, if you follow three trees, you would create three SEINet occurrence records – not one record for each visit.

Go to: https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet/profile/index.php?refurl=viewprofile.php

and create an account. It’s free. There may be a day or two delay before the account is created, but when complete, you will log in and look for the “My Profile” link on the far right. The profile page consists of three tabs, click on “Occurrence Management”, then “Add a New Record”.

Look up specimens in SEINet to see how botanists typically describe their collection localities, habitat, substrate, etc. Some of the links I added to the photographs in previous pages will open a window with occurrence data that will help you organize and compose information for inputting.

The bottom section of the form, “Curation”, leave all blank. For “Basis of Record” select “HumanObservation” from the drop down and for “Processing Status” select “Pending Review”. At the bottom of the SEINet Add New Record form select “Remain on Editing Page (add images, determinations, etc)” then click on “Add Record”. The form will repaint, adding several tabs across the top. Click on “Images” to upload your pictures of the tree, flowers, and leaves.

Below you will find a screenshot of the SEINet New Occurrence Record with explanations of the fields you need to fill in and how to do it.

How Often to Visit

When flower and leaf emergence begins it goes quickly. You may not notice much of a change in one day, but two or three days will produce noticeable differences. The flowers and leaves develop over the winter in nutlike shells at the tips of twigs. When the tree senses the time is right (photoperiod and temperature signals) buds burst open and leaves and flowers fairly pop out. You will want to see this happen. If, like most people, you can only do this on weekends, visit the site and find and mark your plants well ahead of time. Then you should be able to at least bracket the critical time of leaf and flower emergence. Therefore, I recommend weekly visits as the ideal, but once you see things happening you may well want to schedule visits for mid-week at least once or twice.

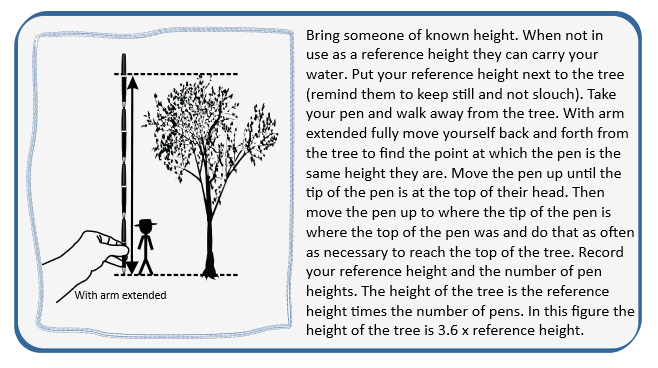

How to Measure the Height & Diameter of a Tree

The “All In” data asks for the height and circumference of subject trees. Measuring the circumference requires a rope long enough. Wrap it around the trunk and measure the length that wrapped around and record that. Bring a retractable measuring tape with you in the field. A big tree can be more than 4 meters (13 feet) in circumference. Measuring the height of a tree is only slightly more involved.