Plant Profile: New Mexico Thistle

Posted on Feb 28, 2021

Stop Before you Chop

By Kathleen M. McCoy, Master Naturalist, AZNPS Phoenix Chapter Member

Leer en español

During early spring, the young Cirsium neomexicanum has already grown about 1 foot on its way to 6 feet in late summer. This prickly member of the Sunflower family (Asteraceae) is often considered a weed, unwanted, and dangerous. Before looking for a scythe, let’s take some time to evaluate this native desert plant.

Photo credit: Lisa Rivera

Common names for C. neomexicanum include New Mexico thistle, Desert thistle, Foss thistle, Lavender thistle, and Powderpuff thistle (Southwestern Desert Flora, 2020). It is scattered throughout most of Arizona as well as CA, CO, NM, NV, UT, and northwest Mexico, residing in multiple habitats, such as plains, hillsides, washes, roadsides, and even urban alleys.

From March to September, it produces pink, purple, lavender, or white fragrant and showy flowers up to 3 inches. The flower head is composed of many small flowers (florets) surrounded by modified or specialized leaves (brachts). The lower, outer brachts point downward, while the upper, inner bracts point upward and are somewhat twisted.

Photo credit: Lisa Rivera

True thistles have spines along the leaf margins (Sivinski, 2016). New Mexico thistle’s spiny green or greenish-gray leaves have the lobes arranged on either side of a central axis like a feather (pinnately lobed) and can be up to 7 inches long.

Arizona and New Mexico each have 19 species in the genus Cirsium (Southwest Desert Flora, 2020). Native thistles support a wide variety of native pollinator and plant-eating insects, such as bees, butterflies, and moths by providing important habitat and food sources. Because native Cirsium spp. can be annual, biennial, or perennial, their nectar can help support pollinators year-round. In addition to drawing nectar and pollen from the flowers, many insects feed on the leaves, stems, and seeds.

Also, many songbirds are attracted to thistle seeds. A symbiotic relationship exists between American goldfinches and native thistles. Seeds and thistle down are food and nest building components critical to the bird’s survival. The timing of seed production and thistle down is related directly to the goldfinch breeding season. Because thistles are late bloomers and American goldfinches breed late in the summer, these birds have an abundance of seeds and thistle down to line their nests (Deane, n.d.). In return, the birds spread the thistle seed to additional areas.

Like its cousin the artichoke, New Mexico thistle is edible! Thistle stalks and taproots are sources of food for humans, but harvesting time is critical. Before the flowering stalks emerge, the taproots of young first-year plants can be dug up. At this early stage, the roots are tender and can be eaten raw or chopped up and added to soups or stews. Their texture has been described as crisp and crunchy with an almost nutty flavor. The stalks can also be consumed, but must be harvested when they are only about 1 to 2 feet high. (Beyond about 2 feet high the stalks are too fibrous and tough to eat.) Stalks can be peeled and eaten fresh or as a cooked vegetable. No significant medicinal uses for New Mexico thistle have been documented (Kane, 2020).

Photo credit: Lisa Rivera

Most southwestern native thistles, including the New Mexico thistle, are non-aggressive and non-invasive (Karr, 2017). Native Cirsium spp. pose no fire risk and do not destructively displace native plants, thus remaining in equilibrium with other native flora. However, native thistles do reduce opportunity for invasive non-native thistles to populate a location.

Despite their benefits, native thistles are either knowingly or unknowingly killed simply because they are considered spiny “weeds.” In some areas, native thistle species are in danger of being complete eradicated. So, please, “stop before you chop!”

Sources:

Deane, G. (n.d.) Thistle: It’s That Spine of Year. http://www.eattheweeds.com/thistle-touch-me-not-but-add-butter-2/

Kane, C.W. (2020). Sonoran Desert food plants. Lincoln Town Press, USA.

Karr, L. (2017). Think Twice Before Killing Those Thistles: Thistle Identification. https://weedwise.conservationdistrict.org/2017/thistle-identification.html

Sivinski, R. (2016). New Mexico Thistle Identification Guide. http://www.npsnm.org/education/thistle-identification-booklet/

Southwest Desert Flora. (2020) Cirsium neomexicanum. http://southwestdesertflora.com/WebsiteFolders/All_Species/Asteraceae/Cirsium%20neomexicanum,%20New%20Mexico%20Thistle.html

Invasive & Toxic Plants

Posted on Feb 01, 2021

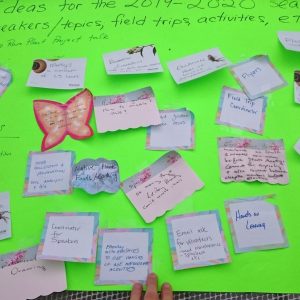

The theme of the Winter 2020 issue of The Plant Press is invasive and toxic plants in Arizona. At our Chapter meeting in January, we had an engaging discussion about the articles and our experiences with invasive and toxic plants.

It was no surprise that most of us have experienced issues with stinknet (Oncosiphon pilulifer/piluliferum). To try to control stinknet on your property, our recommendation is to continually be on the lookout for it during the winter/spring season and take immediate action when you find seedlings. The top methods methods we’ve used to try to control stinknet and other invasives are:

- manual removal;

- hoeing or raking;

- chemical herbicides;

- applying a layer of mulch, landscape fabric, or cardboard; and

- natural herbicides, such agricultural grade vinegar.

Stinknet plants flowering. Photo credit: Lisa Rivera

Oleander (Nerium oleander) is a toxic plant that has been problematic for some of us. We also felt more could be done to inform the public about which landscaping plants and weeds are toxic to humans and animals. Therefore, our Chapter plans to provide more information about toxic plants in the future.

Oleander is a common ornamental plant. Beware, it is poisonous to humans and animals. Photo credit: Lisa Rivera

If you couldn’t attend our meeting, you can still learn about Arizona’s invasive and toxic plants by reading the this issue of The Plant Press, particularly pages 1-24 and 27-31. The publication is freely available to everyone.

Also, if you need help identifying the most prolific invasive species in our area, Desert Defenders has a useful invasive plant fact sheet.

Plant Profile: Desert Globemallow

Posted on Jan 17, 2021

A Most Remarkable Native Plant

By Kathleen M. McCoy, Master Naturalist, AZNPS Phoenix Chapter Member

Leer en español

What plant with stunning petals could you see growing in an alley, a xeriscape garden, and the Sonoran Desert? Most likely the correct guess is Sphaeralcea ambigua, more commonly known as desert globemallow or apricot mallow.

The genus Sphaeralcea (globemallows) contains about 50 plants primarily in North America, and most have flowers in the orange to red range. The most drought tolerant member is the desert globemallow. This largest-flowered globemallow blooms most heavily in the spring, but continues to flower through November. Each bowl-shaped flower has five petals that are up to 1.5 inches long. Once the flowers have faded, small green cups will form, sometimes containing hundreds of seeds. This low-maintenance plant will re-seed itself and can provide surprises in color production; the seed you plant one year may produce plants with a different color the next.

Desert globemallow in bloom. Photo credit: Lisa Rivera

This perennial subshrub’s foliage is a characteristic silvery color with tiny star-shaped wooly hairs, two adaptations that conserve moisture and reflect sunlight. With slightly woody stems restricted primarily to the crown, each desert globemallow grows in a large, rounded clump to a height of 20-40 inches, and may have over a hundred stems growing from the same root. Transplanting globemallows may be difficult and disappointing. The plant above ground may have lateral roots that extend three feet below the ground. If the root is not completely intact when digging up or putting the plant back into the earth, the plant may be mortally wounded.

Desert globemallows can be found in parts of AZ, CA, NM, NV, and UT, as well as Sonora and Baja California in Mexico. You will most likely find this plant growing in desert scrub below 3500 feet on dry, rocky slopes, edges of sandy washes, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It requires full sun and well-drained soil.

This drought-adapted plant can be used in range revegetation. Desert globemallow is an early colonizing species and may suppress invasive species in areas affected by fires. Seeds can be used on construction sites for erosion control or to restore the native plant community. Seedlings have been used to revegetate abandoned mine sites.

Although desert globemallow is edible, it unfortunately does not have a taste to match the brilliance of its flowers. However, it is a food source for the desert tortoise and provides browse for bighorn sheep and livestock. In addition, the large number of flowers produced throughout the year provides a steady source of pollen and nectar to many pollinators, such as hummingbirds, native bees, honeybees, butterflies, and moths.

The hardy desert globemallow has a prominent history in the Southwest. Its stems were used by the Yavapai to create trays for drying saguaro fruit or slabs of pounded mescal. Our ancestors also discovered that desert globemallow relieved and/or cured many disorders. Native Americans have used its leaves and roots to make medicine and eyewashes. Due to its high mucilage content, the plant has been used orally for coughs, colds, diarrhea, and the flu. As a poultice, globemallow has been applied to cuts, burns, snake bites, and swellings like rheumatism.

This lovely native plant is neither threatened nor endangered. The only “problem” is that once established, they and their abundant progeny may aggressively take residence in spaces reserved for other plants in the garden. Most desert globemallows spread by rhizomes. If you plan to contain them, be prepared to pull up lots of suckers. The desert is another matter; stand back and watch the plant spread its glowing blossoms as far as the eye can see.

Sources:

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Plant Data Base: Sphaeralcea ambigua. https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=spam2

SEINnet. Sphaeralcea ambigua. https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet/taxa/index.php?tid=3800&taxauthid=1&clid=0

Water Use It Wisely. Plant of the Month: Globe Mallow. https://wateruseitwisely.com/plant-of-the-month-globe-mallow/